Building a Clojure(script) game with websockets and Reagent

Background

I like making websites, and I like functional programming, so lately I’ve been dabbling with various frameworks and languages designed for functional programming in the web. After trying React and Elm, I knew Clojurescript was the next frontier to explore.

My experience with Clojure, Clojurescript, and any lisp dialect for that matter was limited to a handful of beginner Clojure tutorials I dabbled with for fun. However, I was lucky in that my experience in React and Elm translated pretty naturally into Clojure idioms. Both frameworks taught me to write DOM as a function of state. React exposed me to some functional stuff and dynamic typing, while Elm showed me the power and correctness guarantees made possible by immutable data structures and typed functional programming.

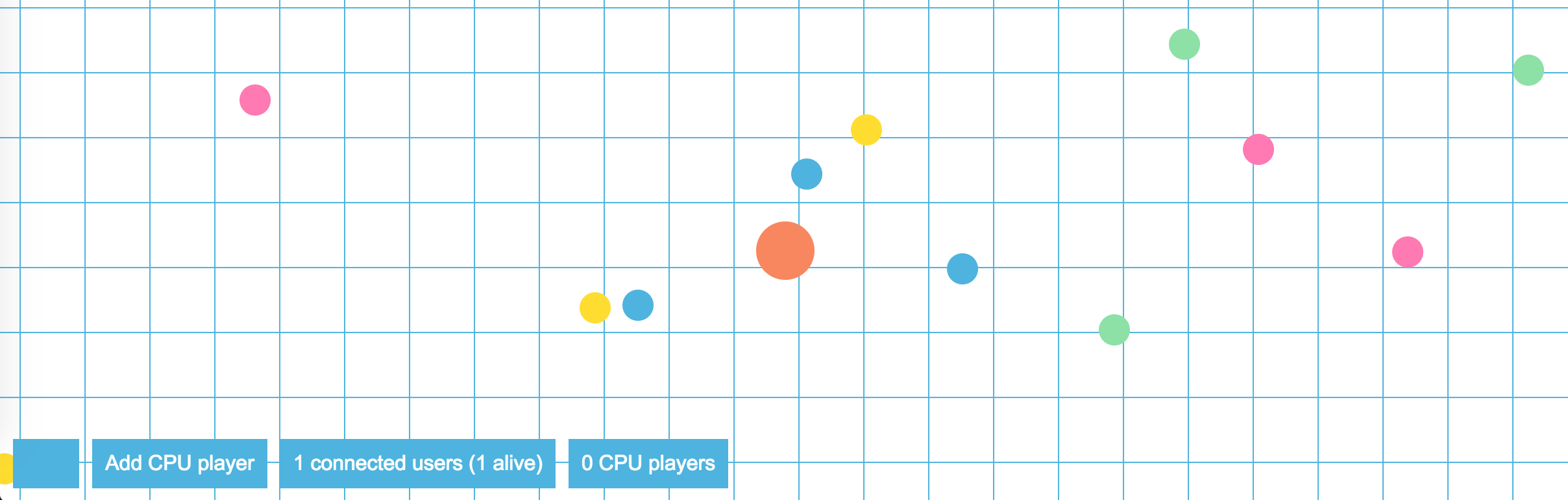

Clojure, like Javascript, offers a one-stop-shop for web development. I knew I wanted to write a full-stack game with a Clojurescript frontend and Clojure backend. Sadly I couldn’t come up with an original idea for a game so I decided to build a copy of the agar.io game, which I could implement with websockets server-side and Reagent (a React wrapper) client-side.

Click here for a live demo of my game, cljs-agar, and click here for the source!

Setting up the server

While looking for a Clojure websockets library, I came across Sente which conveniently had a list of example projects in its readme. One of these examples was Snakelake, a multiplayer websockets game with Reagent that already had Figwheel and a heroku deployment script set up. So, I cloned the repo and began hacking!

Setting up the client

Writing a game in Elm gave me a pretty good idea on how to structure the state for an in-browser game. I followed the Elm architecture’s principle of keeping the entire state in one Model by dumping all of my app’s state into one Reagent atom:

(:require [reagent.core :as reagent])

(defonce state

(reagent/atom

{:remote nil

:uid nil }))

The :remote key holds the single source of truth for my Reagent app, and it’s the data structure all my React components inspect while rendering. It’s named :remote because it’s a Clojure map provided by the server, and it looks the exact same for every connected user. On the other hand, the :uid key holds the connected user’s unique identifier, and is therefore different for every user.

Client server communication

As I alluded to above, my Reagent app gets all its data from the server. In other words, I have just one Clojure map representing the entire game that gets sent from the server to the client via a websocket connection. Here’s a snapshot of this map:

{:player-counter 1

:players {e-32 {:color #FEDD30

:alive true

:type :edible

:radius 12

:position {:y 94, :x -697}

:velocity {:y 0, :x 0}}

1 {:color #8DE0A6

:alive true

:type :user

:radius 18

:position {:y -361, :x -138}

:velocity {:y -0.012, :x 0}}}}

Although this map exists in memory inside my client app as well as my server, it means different things to the client and server:

- Client: Every connected user has one copy of this map hanging around in their browser’s memory. From a code perspective, this map is located in the

:remotekey of my global Reagent atom. The DOM presented to every client is a function of this map and the user’s identifer. The client is only able to read to the map, and never writes to the map. - Server: The server holds exactly one copy of this map, and is uniquely responsible for coordinating updates to the game state. When the server starts up, it jumps into an endless loop that calls a ticker function every 25 milliseconds. The ticker function looks at the velocities and positions of players to determine their next positions and velocities, then pushes the output down to the client with the

broadcastfunction so they are kept up-to-date with the game state. As implied by its name, thebroadcastfunction announces the game state down to every connected user. So as long as a user maintains a connection with the websocket, they’ll have an up-to-date snapshot of the game state!

(defn ticker []

(while true

(Thread/sleep 25)

(try

(update/tick)

(broadcast)

(catch Exception ex (println ex)))))

Sharing one game state across the client and server definitely made development easier and faster. Having a solid understanding of that one Clojure map enabled me to write server side updaters that updated velocities and positions, and Reagent components that decided where on the page a player should be rendered as a function of their position.

The shared state is just the tip of the iceberg, though. You could technically get that with NodeJS and your favorite JS framework. What makes the Clojure/Clojurescript combination so compelling are the shared programming idioms of persistent immutable data structures, pure functions, and functional programming paradigms. I was able to switch between working on backend and frontend with zero loss of productivity!

Developer experience

Long story short, Figwheel makes interactive development extremely streamlined and joyful. The author’s talk and demo is highly convincing.

Overall thoughts

I have to say I’m stunned by Clojure’s versatility and reach. If you think about it, Clojure does stuff that Java does and now Clojurescript does stuff that Javascript does. People are also working on bringing Clojure to mobile development, which leads me to believe that if enough people adopt Clojure, we could have Clojure solutions to any kind of high-level programming problem.

I went into this project half-hoping to find out whether I liked statically typed or dynamically typed functional programming more. They both seem wonderful in their own ways, so I’ll probably have to dig deeper into Clojure (especially clojure.spec) and check out the languages that inspired Elm to gain more insight.